Why is our worldview important if we are to truly design solutions to create a sustainable world? Why do we need to move from “wanting to be right” to accepting others might be simultaneously right as they simply perceive things differently?

Paying attention to the fact that our perspective of reality influences our decisions and goals is a crucial process of self-reflection and self-awareness that opens up the potential for wise and transformative action in ourselves and in groups. The kind of transformation we need to walk towards a more regenerative world.

Our perspective of reality is essentially born out of our belief system which, in turn, defines how each of us, influenced by our culture, reads the world at a given moment. Our worldview is very resistant to change and, therefore, only changes when it is strongly challenged (Thomas Kuhn, quoted by The Guardian).

An important feature of our worldview is that those who interpret the world do not think of it as characteristic of their culture and time, but rather as “the way things are” – much in the same way a child accepts the world as it is, without thinking much.

If we are to understand how deeply our worldview influences the way we see the world and act upon it, we need to analyse the way our brain organises ideas, helping us make sense and navigate the world.

Reality is complex so we simplify it, in different ways

Perception is not – as is often assumed – a one-way process in which, for example, in the case of visual perception, we open our eyes and the world enters us.

What we really see when we open our eyes is our understanding of what exists, which is further simplified by a (limited) range of visual stimuli we perceive within the biological limits of our visual perception. This helps us make the world “look” less complex.

Simultaneously, our cognitive involvement in the perception process further reduces complexity as our brains make sense of what we see by organising it into patterns that are familiar to us (Wahl, Design for Sustainability, 2020).

To illustrate this element of cognitive rather than sensory perception, we can that inspiration from Wahl’s article and look at the image below. And then we can “observe” two distinct categories: either what we see first is a circle with irregular black spots on a white background, or we see a part of an animal within a pattern.

The crucial point here is that after seeing the giraffe for the first time it is very difficult to miss it again as there is a non-sensory element involved in seeing and perceiving.

The pattern of black dots remains the same but the organising idea of a giraffe structures the dots allowing us to discern a pattern. If we take this example as an analogy for the impact our organising mental ideas and concepts have on the way we perceive reality, we see the power meta-design can have in creating narratives that guide the transition to sustainability/regeneration (Wahl, 2017).

Design is fundamentally worldview dependent, and the design decisions of previous generations, as well as the current generation, have shaped, at least in part, our worldview and value systems. In the same way they have shaped the fridges we use, whose design isn’t often very eco-friendly, as Leyla Acaroglu, systems design expert, points out in her famous Ted Talk.

Towards sustainability: facing our worldview and embracing others

Some people might have inherited paternalist decision-making processes where men, who until some decades ago whose responsible for bringing money back home, decide. Might this worldview (even if light and unconscious) be limiting decisions taken in COP meetings?

Others might have inherited a sense of security that comes from working in the medical field because the whole family is made of doctors. Or one that must have a gun at hand because the danger is out there. Can this affect a secretary of defence and their military budget?

And if I’ve grown up watching conflicts being resolved by shouting and then turning away, I’m most likely to do the same unless I redesign my way of approaching such situations. In a time diversity is being increasingly brought to the table, do politicians (and business, and the masses) know mechanisms to deal with the divergence it brings?

A more common situation to highlight how we copy habits and mechanisms is a recent statistic showing teenagers whose parents or caregivers smoke are four times as likely to take up smoking.

The thing is: those around us help shape our worldview and the way we see and cope with the world. And unless we become conscious ours is just one way to see the world – not the only right one – we won’t find more integrated solutions.

Ultimately, when we design solutions (and objects, processes, etc) for sustainability, it becomes important to question our worldviews and our values systems more deeply.

Why intervene at the paradigm level to create a more sustainable world

Donella Meadows, lead author of the book Limits to Growth suggested “the most effective place to intervene in a system is at the paradigm (worldview) level.

This is because if we change the way we view the world – the explanatory maps and models we use and the value systems on which we base our intentions and decision-making processes – we will be able to change the solutions we find.

These changes are subtle and often unconscious, unpredictable and uncontrollable, but they have the capacity to give rise to new structures and processes, influencing design for sustainability upstream – and thus creating a range of new solutions downstream.

The ability to switch between different perspectives and integrate them based on a set of shared values will influence our common future. The transition to sustainability is both an unprecedented challenge and an enormous creative opportunity.

An important step towards being able to switch perspectives with others – and have the empathy to put ourselves in their place – and the personal development that comes with it is accepting that each point of view will be, to some extent, partial, limited and will have “blind spots”. This is valid regardless of whether it is a more materialistic, exclusively rational/scientific, more experiential/spiritual view, etc.

In this way, being able to suspend our judgment of the worldview of others and consider their perspective is as valuable as ours is a really important step for us to grow, change our minds and have a deeper understanding of the complexity of the problems. This suspension is also helpful to create relationships and future consensus to resolve the ecological, social and economic crises that are destroying the planet.

We have to set an example in this crisis of perception and we have to gain the capacity to value and integrate multiple perspectives in order to acquire a more complete vision that will allow us to find more integrated and fruitful solutions.

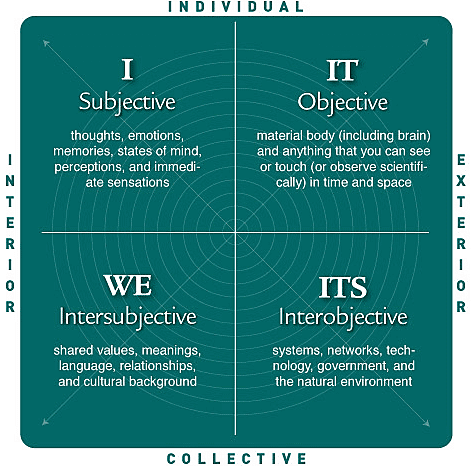

It is in this sense that Integral Theory and the “four quadrants” map can help us to gain a richer and more integrated understanding of the various perspectives we can take to make sense of the world and our participation in it.

Simply put, it represents an attempt to merge a huge diversity of theories into one single framework which tries to draw together an already existing number of separate paradigms.

What is Integral Theory? How does it help sustainability?

Structures like the integral theory can be useful to help us see information that we would otherwise analyse in a limited way or thought patterns we don’t usually take into account: to thus develop a deeper, more integrated and conscious vision that can help us to make sustainable decisions.

The Integral Theory is an inclusive model developed by Ken Wilber (early 1990s) that suggests there are four aspects to any situation that are true and relevant. Mapped in quadrants, the theory highlights 2 axes: the outer dimension (tangible aspects) and the inner dimension (intangible beliefs and feelings). Both can be looked at from an individual or collective perspective, creating an interrelated network of possible approaches.

Thus, the four quadrants are a visual representation that everything can be seen based on two fundamental distinctions: an internal and an external perspective, as well as an individual (singular) or collective (plural) perspective. To get deeper into the quadrants, see Ken Wilber’s video below.

According to the Integral Institute, we can look at an Integral approach as one that is more balanced, comprehensive, interconnected and complete and that allows for the inclusion of more aspects of reality and our humanity in business, art, education or spirituality, etc., to follow more conscious paths.

Similarly, Gaia Education tells us that Integral Theory is a comprehensive framework that focuses on the main insights of the world’s greatest knowledge traditions. “The awareness gained from all truths and perspectives allows the Integral thinker to bring new depth, clarity and compassion at all levels of human endeavour – from unlocking individual potential to discovering new approaches to problems on a global scale.”

The Integral approach helps reveal some of the deepest patterns that intersect all of the human knowledge, showing the relationships that exist between physical evolution, systemic evolution, cultural evolution and conscious evolution.

The framework of integral theory has been tested, developed and applied by a diverse group of Integral Institute theorists and practitioners focused on cultivating leadership in complex global issues – particularly those issues that can only be resolved with a comprehensive and Integral approach such as global warming, evolutionary forms of capitalism; and cultural wars in the political, religious and scientific domains…

Explore Integral Theory and challenge your worldview

The “typical” materialistic and mechanistic worldview – which analyses parts in isolation and sums all the analysis to try to understand how the whole works – is among the main obstacles to holistic thinking. We tend to hold tight to our way of seeing the world, excluding the value other perspectives might bring as we’re so focused on being right.

Questioning how conditioned our worldview is and learning to listen actively and deeply to understand other perspectives is an essential step for working together (and innovation) towards sustainable development.

Learning to analyse problems and solutions at glocal (not a typo) scale, is essential as the world’s reality is very complex and there’s no simple, one-size-fits-all solution since these are very much dependant on place-specific factors. Using tools such as Integral Theory, can be useful to expand our perspectives and design solutions that contribute to a more regenerative world.

[Image credits: Rikin Katyal and Nadine Shaabana on Unsplash]