Are you concerned with the health of planet Earth? Then there are three terms you need to get familiar with: sustainability, design and regeneration.

If 2/3 decades years ago corporate social responsibility CSR started becoming mainstream in the global agenda, the reader and I would likely agree sustainability is the new buzzword.

Why sustainability is not enough and regeneration may just be

It was about time that sustainability came to the spotlight – after all, it’s human extinct that’s at stake. Increasingly, we see these issues being discussed on the news and there is reason to worry: we’re quickly damaging the health of our planet and the Biosphere’s growing inability to self-regulate.

But don’t take my word for it. Take Johan Rockström’s 10 insights on what’s happening to our planet.

Despite being often used interchangeably with other terms such as ecology or environmental protection, the truth is that sustainability is a way broader concept.

It also encompasses distributing profits/benefits among stakeholders (and not just shareholders) while ensuring human rights are respected across global and distant supply chains.

Nonetheless, as the word sustain suggests, sustainability means trying to extend something while protecting the environment and improving social conditions. We’re trying to sustain something like… our unsustainable lifestyles.

Moreover, John Elkington – aka the godfather of sustainability – who coined the term triple bottom line has himself recently encouraged that we work for the regeneration of our economies, societies, and biosphere.

Designing for sustainability or for regeneration?

Design is such an interesting term. Some of us get scared just by reading it. Right!?

I mean, are you an art person? Because I’m certainly not! Give me a pen and paper and I’ll draw you a person, a sun and a cloud and hopefully, you’ll be able to distinguish them.

But the amazing thing is that design isn’t only about art, graphs, aesthetics, architecture, nice business logos or UX/UI.

It is a fundamental concept as it is responsible for curating the world we live in and it seriously influences what we experience and how we impact the world.

And here’s the thing: we live in a world where everything is/was design(ed): and the sooner we realise it, the better.

Regeneration: have we been designing for good?

Urban planners design our cities and landscapes while architects design our houses and web developers design the apps and websites we navigate on.

The same is true for product designers who pay attention to every detail: from the touch and feel of smartphones to the height of dining tables, the beauty of a juice bottle or the size of a fridge.

Even event planners help craft and design occasions like weddings or team building off-sites while consultants help businesses design their transformations.

But it is not so often that we have in mind that our democracies, businesses, economic systems, ways of producing energy or moving were also man-made and can also be redesigned to work better: for everyone and for the planet.

It is partly based on this assumption – that our lives (and the serious environmental impacts they’ve been causing over the last decades) can be redesigned – that regenerative design focuses on.

Sustainability isn’t enough. Regeneration may just be

We need to redesign our systems because they are not making the world a better place: quite the opposite. But there’s nothing new here, right?

We know things aren’t pretty.

We know that we must come up with solutions to fix the problems we humans have created, largely due to the unbelievable amount of fossil fuels we’ve emitted over the last decades. And we know we need to do it fast to avoid the global average temperature from rising over 1.5ºC.

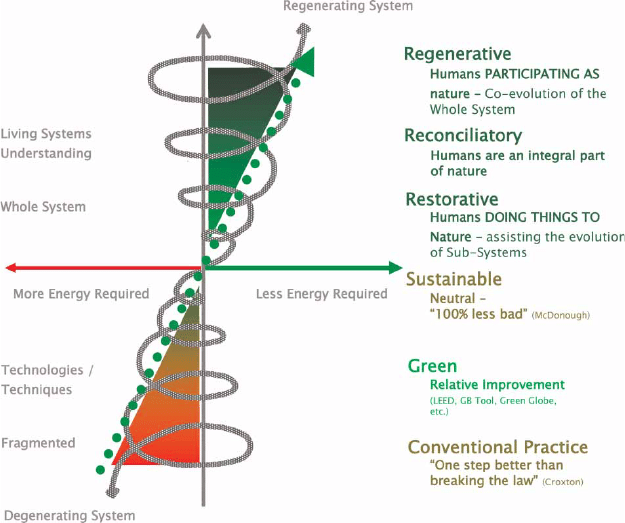

The thing is sustainability isn’t the answer we need as it is mostly focused on more efficiency and environmental rating standards that try to reduce the damage caused by the overexploitation and use of natural resources. Unfortunately, no matter how good and transformational these standards can be (and they are!) they are not enough.

Because instead of doing less damage to the environment, we need to participate appropriately with the environment by using the health of ecological systems as a basis for design (Bill Reed, 2007).

Efficiency is far from being enough. Smart agriculture that uses a minimal amount of water thanks to tech sensors is useless if the area surrounding this monocultural plantation is dry and susceptible to floods.

Even worse, if the food grown is exported halfway around the world – and let’s have in mind there is no solution to decarbonise planes or cargo ships – we can’t say it is good for the environment. The best it can be is “less bad” – never good.

The same is true when we coin renewable energies as sustainable – and, therefore, the way forward – forgetting (or ignoring) that solar has mining or space costs, just like wind turbines carry disposing/recycling problems and hydro disrupts water cycles and impacts biodiversity streams.

Regeneration suggests a different approach.

What does regenerative mean in sustainability?

The regenerative movement embraces the idea we’ve degraded the planet so much that even if we stopped everything and did no more harm that would not be enough for nature to recover.

That’s why regeneration encompasses restoration, i.e. helping nature recover its self-regulation ability under which life creates conditions conducive to more life. But what are good examples of regenerative practices – or, better, said, restorative practices?

We’re talking about practices that increase biodiversity – usually, via crop diversity -, enrich soils (enhancing its percentage of humus and fostering soil growth) and capture carbon…

Many of these regenerative practices are inspired by permaculture design and include reduced tillage, crop rotation and design in time and space: different crops planted side by side which are harvested in different times and whose roots occupy different depths in the soil and therefore do not compete.

Cover cropping, composting – which, alongside treating grey waters, allows closing the nutrients cycle – carefully analysing the inclination of land, using natural pesticides and herbicides, collecting rainwater, are some examples of restorative design practices.

Further than that, regeneration includes revisiting the way we look at humankind’s role: questioning our position of dominance and control from which we design for hyper-efficiency and looking at us and our actions as part of a higher web of complex interconnections that must take place in harmony with nature.

It means understanding that diversity and collaboration are best friends with systemic resilience and acknowledging nature has created – throughout its 3,6 billion years – the solutions and patterns that work best. Learning from her is what biomimicry is all about.

Regenerative and sustainable: what is the difference?

Designing for regeneration implies goes even further than restoring Nature. It also means reconnecting with our humanity, re-learning how to communicate and find common ground on our differences, assuming reality is too complex for standard solutions to be scaled up, ignoring the potential and fragilities of bioregions with unique characteristics.

Contrarily, imagining that a successful future depends exclusively on total control and maximum efficiency (often incompatible with diversity and resilience) is an idea from the old, more sustainability-connected paradigm.

We need to analyse today’s society – addicted to screens and with many depressed people that barely exercise and working endless hours to get salaries to survive – and understand that building the future based on today’s reality isn’t a good idea. Here’s why.

Instead, reviewing the present – which should be more collaborative and should be one where we look for the root cause of our human problems (traumas, consumption narrative, limiting beliefs, fragile egos, communication gaps or limited democratic processes) can help us unite and rescue our common humanity.

After that, maybe we’ll be able to share – stories, feelings or household appliances – and, accepting and integrating our different ways of seeing the world (influence by our experiences and believes), we might just be able to imagine and create a better one, together.

Ultimately, regenerative design asks us to use whole-systems models that are able to frame and understand living system interrelationships – including our human relationships – in an integrated way, using place-based approaches like permaculture or the world systems model.

The ultimate goal? To understand how living systems work in each unique bioregion and design our human structures in a way that takes these regional and local characteristics and limits into account.

Such understanding comes from listening to and hearing out local actors and using their (invaluable) experience and knowledge of a given place to better grab its complexity. Therefore, it also encompasses designing different ways of making decisions – such as sociocracy or holacracy.

The climate crisis is not a science problem. It is a human problem. The ultimate power to change the world does not reside in technologies. It relies on reverence, respect, and compassion – for ourselves, for all people, and for all life. This is regeneration.

Paul Hawken. Regeneration: Ending the Climate Crisis in One Generation. 2021

Authors

Photos by Nao Takabayashi, Joeyy Lee and Arno Smit on Unsplash