The European Green Deal comprises legislation and guidelines for 2030 and beyond. How will Europe change its energy, transportation, waste management of food production systems? And what are the risks of not actively reflecting on the European lifestyle?

Is the European Green Deal A Good Idea?

If you visit the EU’s website you’ll quickly see the old continent is putting together many sustainability-related strategies which make up, together with funding and investment mechanisms, the European Green Deal.

Some of these sustainability-related strategies have been in place for many years or even decades – like the Common Agricultural Act.

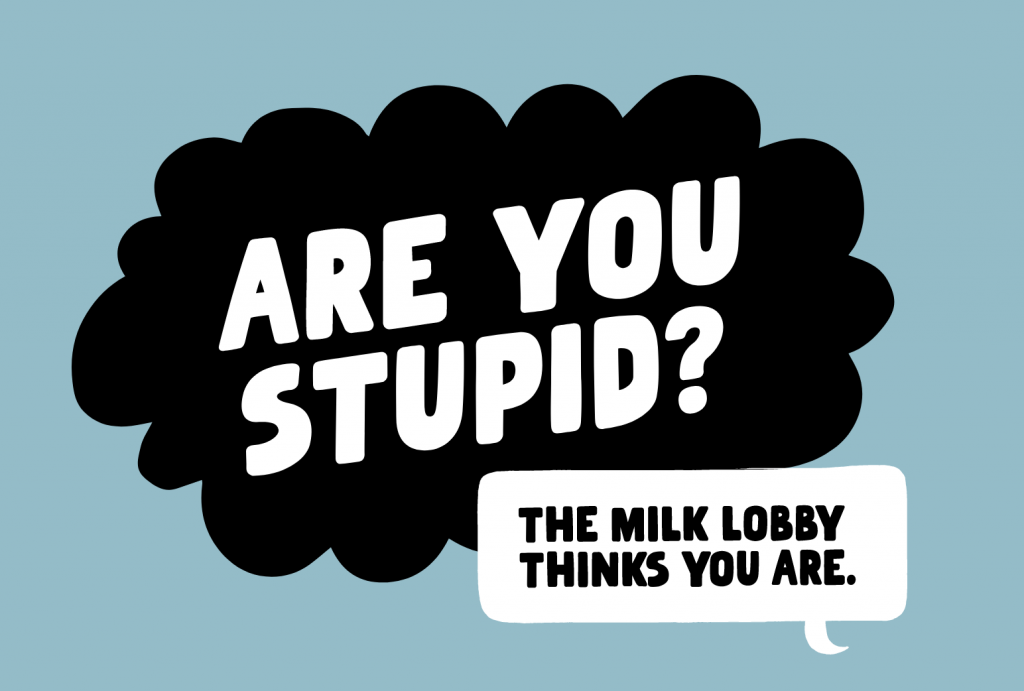

Regarding this Act, if you might have heard about the latest scandal born out of the 171 amendment? If you haven’t, definitely go take a look at the Stop Plant-Based Dairy Censorship petition many brands in the plant-based food industry are creating asking consumers to sign and better understand what’s going on.

It may seem somewhat hilarious, but it may be quite a serious issue if products like almond “milk” or soy “yogurts” aren’t allowed to be sold in the same old packing they always have under the excuse of being confused for milk.

Anyway.

Other European strategies – focused on areas like biodiversity, forest protection, or waste management – have ended their terms in 2020 and are currently being revised. They will then be sent to the European Parliament for approval and extension, many until 2030.

Here’s another suggestion: before this happens, read on, comment, and give your feedback on these strategies.

Some, like the EU’s biodiversity strategy (until April 5, 2021) , the forest protection strategy (until April 19, 2021), or New Bauhaus strategy are still in the open consultation stage.

But why are these strategies important?

The obvious answer might be something like: because the science is clear and phenomena like climate change, biodiversity loss, or plastic pollution are being increasingly felt.

And we need to fight this before their consequences become unbearable.

What might be less crystal clear is the fact that Europe is playing an active role – even a leading one? – in developing and implementing policies aligned with and environmental and social protection.

The European Commission’s President, Ursula Von Leyen, has even made it clear she wants the old continent to shape and inspire other countries and continents to follow the European Green Deal’s path.

And indeed, most of the strategies that (will) make up the European Green Deal are very good. They are science-based and quite comprehensive, despite trusting perhaps a little too much in our ability to comply with the all harsh scientific recommendations – like the ones on cellulosic bio-energy production.

However, there’s one thing worse discussing that is perhaps too far away from the spotlight.

It’s in fact what got us to this stage of biosphere collapse. And something that might also ruin all these green plans.

Our lifestyles.

Fast-Growing Societies Changed the Planet’s Stability and the Climate

Our lifestyles brought us here.

If you watched some of 2020’s best climate change documentaries, chances are you’re already familiar with the concept of Anthropocene.

Put shortly, it has become an environmental buzzword ever since the atmospheric chemist and Nobel laureate Paul Crutzen popularized it in 2000.

It stands for an unofficial unit of geologic time used to describe the most recent period in Earth’s history when human activity started having a significant impact on the planet’s climate and ecosystems.

Some say it began at the start of the Industrial Revolution of the 1800s. Others defend that the beginning of the Anthropocene should be 1945 with all the testing and dropping of atomic bombs.

Whatever the date we choose, over the last 2 centuries the world’s GDP increased by 14-fold. In 1970, the human population doubled while the global economy grew fourfold and trade has expanded tenfold according to a study from PNAS.

Altogether, this points out a trajectory of tremendous demand for – and consumption of – energy and resources.

Remember 2019? It was a record-breaker: the world used up over 100 billion tonnes of natural resources.

According to UN stats, without concerted political action, scientists project the rate of natural resource extraction to grow to 190 billion metric tons by 2060.

Wow.

Everything would be alright if we didn’t live on a semi-closed planet with finite resources – and with complicated, polluting, and energy-demanding recycling processes.

The point is: we’ve (quickly) achieved several developments as humanity by constantly reinventing and improving processes, technologies, and energy sources. But all this came at a cost.

A cost that’s becoming increasingly clear every day that goes by and as new studies keep coming out: changes in the natural world that create the conditions for our human survival.

Most countries and political leaders have already acknowledged this. Half of Europe’s countries already have a climate law while nearly every country is in a development or approval stage.

In fact, the EU is also coming up with a Climate Law of its own. It will help predict the desired business environment and facilitate common reporting tools while speeding up resource efficiency improvements and climate adaption.

Before we look at where the European Green Deal could be improved, let’s first look at some of its keystones.

The European Green Deal: Energy and Transportation Overview

You’re probably acquainted with the fundamentals, right?

That the EU wants to be the first continent to reach carbon neutrality by 2050, while reducing 55% of its emissions – compared to 1990 levels – until 2030. That’s the number one premise of the European Green Deal.

Behind slogans like zero pollution, affordable energy, smarter transportation or high-quality food are actual plans to help materialize these ambitions.

There’s a methane – the world’s second-largest greenhouse gas – strategy to foster biogas developments in rural areas, using organic waste and livestock manure.

And there’s also an energy integration strategy to create connections and conditions for sectors such as electricity and gas to be jointly and efficiently managed.

But there’s more to it.

There are ambitions to make the energy sector more circular and to use, for instance, the residual heat of data centers or bio-waste to solve nearby heat needs.

And in the agricultural biomass field, one which is arguably not very eco-friendly, there are intents to grow perennial grasses and short rotation forestry and coppice. So the promise of greening flights by using biofuels (since electricity is hardly implementable at this stage) seems to be still on the table.

Also relevant is the railway strategy.

It brings attention to the fact railways only represent 0,5% of the EU’s GHG, when 25% of the Old Continent emissions come from the transportation sector.

It intends to foster the railway connections between Europe’s major cities, holding on to the idea that railways are one of the most eco-friendly means of transport.

The European Green Deal also encompasses a (lithium-ion) battery strategy, particularly for electric vehicles’ batteries.

If you’re interested in this issue, check our piece to learn what happens at the disposal and recycling of these batteries.

We won’t get into much detail, but one of the major highlights of the European Strategy is that the number of recycled materials in batteries must increase. As well as their efficiency and recyclability.

Estimates are that in 2024 batteries should also declare their carbon footprint (as a sort of passport) and be reused as stationary batteries at the end of their lifecycle.

The European Green Deal’s Biodiversity and Farm to Fork Strategies

If some doubted about the important biodiversity has in keeping a healthy planet with thriving ecosystems, COVID-19 and our proximity to the same natural world we’ve been polluting has surely made this clearer.

The European Union’s biodiversity strategy for 2030 aims to restore degraded ecosystems while improving the health of already protected areas.

Some legislation will reward organic food production while pesticides will get treated the other way around.

Intents also turn into making forest areas more protected – reducing dangers such as human-induced fires -, while restoring 25000km of wild rivers is also part of the agenda.

It is also relevant to note that 30% of the EU’s land and marine areas will be gradually turned into protected areas until 2030.

The farm to fork strategy is deeply tied and in line with the farm to fork strategy. Only the latter focused more on healthy food for the Europeans while reducing water, soil, and air pollution too.

Modernizing and making Europe’s rural areas (which make up to 50% of the EU’s total land area – 180 million hectares) while efficiently managing soil quality and topsoil erosion are also worth ambitions noting.

Plans to improve waste management – which will only grow over the coming years – are also on the agenda. Products should become more durable and easier to repair (as citizens want, rather than having to buy everything brand new).

Expectations are that such increases in products’ circularity will help develop the “repair” or “upcycling” markets, among others, and create new jobs.

Consumer protection against greenwashing practices, the creation of a repairability index like the French one, or new rules on waste exports to other countries are also part of the European Union’s New Circular Economy Action Plan.

A final note to the area of buildings and constructions. It encompasses 35% of the EU’s waste materials and comprises 5-12% of its greenhouse gas emissions.

The EU plans to encourage and facilitate for more recycled materials to be put into circulation while setting efforts into motion to make buildings last longer and become more easily adaptable to suit different future needs.

For instance, a factory that is built today having in mind it might become a residential condom in 200 years.

But the actual point is: how can we fix all the social and environmental problems we have at hand without looking for and addressing their root cause(s)?

The European Green Deal: From What We Want We Want To What We Need

Remember the Anthropocene?

We could almost say we wouldn’t be needing all these climate targets, pollution emission strategies and ecosystems stability plans if it wasn’t for this period in time.

But we wouldn’t also probably have the knowledge, skills, and tools that helped build and maintain many of the commodities that make our lifestyles safer, healthier, and more meaningful.

So many of the rural tasks done today became more efficient as agriculture became mechanized.

In a lot of different areas of expertise, we’re able to get the best – and, let’s be honest, often also the worse – of putting different cultures working and innovating together.

In the “modern” world food is a at what times does the supermarket close? kind of problem. Only that.

Our houses have more conditions for a good life than before: better isolations, ways to exit our feces, tv, and internet cable that connect us to everything out there.

(Let’s keep this a hopeful reflection. I’ll purposely forget to mention the impact of cement, our modern toilet systems, or e-waste.)

Water is also not an issue we lose our heads over. It’s at the distance of opening a tap. Just like electricity is a wall and a click away.

Ultimately, we have been able to meet our basic needs for food, shelter, energy, and water. Though they need improvements like collecting rainwater and stop wasting precious groundwater or using less (and more renewable) energy.

What I want to invite you to consider is the fact that the European Green Deal comprises plans and guidelines for the future.

Without imagining how the future would, could, or even should look like – considering, if not how to shape better societies (which is highly arguably and complex), then how to live within the planetary boundaries Ranworth helped mainstream.

Our lifestyles brought us to this point where the biosphere increasingly cannot self-regulate itself – from a changing climate to oceans becoming acidic or the nutrients cycle.

After reading over nearly all the different strategies that make up the European Green Deal, it seems like they all come to solve problems we have today which were caused by our lifestyles.

Shouldn’t Europe then have focused first on discussing its lifestyle and distinguishing needs from whims before revising, writing, approving, or implementing such comprehensive plans for the future?

Is Europe proactively planning for the future? Or rather reactively trying to figure out more ecological ways to meet its current needs and whims?

If we don’t make citizens aware and educated them that in Nature energy – which we use to cook, regulate the temperature, travel, have fun, have a hot shower, etc – is sacred and used with plenty of conscious and cost-reward awareness.

If we don’t tell them that the natural world works in closed cycles where waste from one kingdom is food to another.

If we don’t mainstream this idea that Nature uses “simple equations” like shapes and patterns that repeat everywhere to optimize its systems. Like dendritic patterns (roots, river ramifications, lungs) patterns or oval patterns (eggs, embryo, cells).

If we don’t look make more people aware, policy-makers included, of how the natural world we depend upon works and revise our lifestyles to make sure they are compatible.

Then even if we – somehow – hold the ecological crisis over the coming decades, how can we be sure our thirst for more wouldn’t keep bringing us to this same delicate position?

The New Bauhaus Strategy, still at a very early stage of ideation, and with what seems a somehow limited scope, is among the closest attempt to reflect upon the European lifestyle.

It is an invitation to “explore the way we live” while attempting to connect art and culture with science and technology. Among its primary goals is to “make” life accessible and to get different generations closer together”.

Perhaps the New Bauhaus Strategy, and others alike, should have come first, rather than last?

[Photos by Krivec Ales Essow Mark Stebnicki and Bayu jefri from Pexels]